Putting TEACHERS Behind the Steering Wheel

Educator Effectiveness Spotlight

Beginning in summer 2016, SREB’s Educator Effectiveness team partnered with leaders and educators from three school districts in central Oklahoma to try something called #MyPD. The goal of #MyPD was to give teachers an opportunity to steer their own professional development using an innovative approach called a community of practice. This approach requires a paradigm shift in the way professional development is conceived by leaders and perceived by teachers.

Watch the video below to find out more about our #MyPD community — and explore the tabs below to learn more about implementing a community of practice in your own state, district or school.

THE BASICS

Click each drop-down heading below to learn about the community of practice approach.

What is a community of practice?

A community of practice is a group of people who aim to do their jobs better by learning together. The two key characteristics of a community of practice are that they are member-driven and action-oriented.

A community of practice is a group of people who aim to do their jobs better by learning together. The two key characteristics of a community of practice are that they are member-driven and action-oriented.

How are communities of practice different than other forms of professional development?

To better understand exactly what a community of practice is, it is helpful to examine how it relates to — and compares with — other more familiar forms of professional development.

Why should states, districts and schools use this approach with teachers?

COLLABORATION >> Communities of practice are rooted in personal and collective progress toward goals. Communities of practice allow for passions, needs, experiences, insights and resources to be shared. Educators are given opportunities to connect with people they may not get a chance to otherwise, such as colleagues from different grade levels, or even different schools or districts.

COLLABORATION >> Communities of practice are rooted in personal and collective progress toward goals. Communities of practice allow for passions, needs, experiences, insights and resources to be shared. Educators are given opportunities to connect with people they may not get a chance to otherwise, such as colleagues from different grade levels, or even different schools or districts.

“I’ve taught 20 years and the thing that I notice the most is we don’t have a lot of time to collaborate. This opens up a time for us in all different areas of education. We come together in one place and collaboratively discuss what the needs are as a united group.” – Teacher and #MyPD Community Member

______________________________________________________________________

EMPOWERMENT >> Educators want their voices heard, but all too often they aren’t. Communities of practice elevate teachers’ voices and collective impact by treating them as the experts on education.

EMPOWERMENT >> Educators want their voices heard, but all too often they aren’t. Communities of practice elevate teachers’ voices and collective impact by treating them as the experts on education.

“They’re the experts in education. Allow them to use that expertise to make education better.” – District Chief Human Resources Officer, Mid-Del Schools

______________________________________________________________________

MEANINGFUL ACTION >> In a community of practice, educators choose the topics they want to engage with, based on common problems, needs and interests. Therefore, the topics they spend time on are ones that are fulfilling and meaningful to them, both personally and professionally.

MEANINGFUL ACTION >> In a community of practice, educators choose the topics they want to engage with, based on common problems, needs and interests. Therefore, the topics they spend time on are ones that are fulfilling and meaningful to them, both personally and professionally.

“We’re not fed the information that other people think that we need — we create that. And because of that, it’s things that will work and that will matter.” – Teacher and #MyPD Community Member

Who are we?

Megan Boren is the Coordinator for State Engagement and Policy on SREB’s Educator Effectiveness team. Prior to working at SREB, she was the Education and Workforce Policy Advisor to former Governor of Virginia, Tim Kaine. Megan has a bachelor’s degree in political science and a master’s in public administration and policy from Virginia Tech. She lives in Charlotte, North Carolina. She loves Hokie football, cooking and going to concerts.

Megan Boren is the Coordinator for State Engagement and Policy on SREB’s Educator Effectiveness team. Prior to working at SREB, she was the Education and Workforce Policy Advisor to former Governor of Virginia, Tim Kaine. Megan has a bachelor’s degree in political science and a master’s in public administration and policy from Virginia Tech. She lives in Charlotte, North Carolina. She loves Hokie football, cooking and going to concerts.

Torrie Mekos is the Communications Specialist on SREB’s Educator Effectiveness team. Prior to working at SREB, she taught elementary school in Nashville, Tennessee. Torrie has a bachelor’s degree in childhood education and biology, and a master’s in Community Development and Action, with areas of focus in organizational development and education policy. She loves Buffalo Sabres hockey, her weird-looking pet dog and eating sushi.

Torrie Mekos is the Communications Specialist on SREB’s Educator Effectiveness team. Prior to working at SREB, she taught elementary school in Nashville, Tennessee. Torrie has a bachelor’s degree in childhood education and biology, and a master’s in Community Development and Action, with areas of focus in organizational development and education policy. She loves Buffalo Sabres hockey, her weird-looking pet dog and eating sushi.

Bev Wenger-Trayner works with organizations and groups to develop horizontal learning partnerships as a way to help them become better at what they do. She works as a a social learning theorist and consultant. The joy of her life is her two-year old grandson who lives in the United Kingdom. They stay in touch using Skype.

Bev Wenger-Trayner works with organizations and groups to develop horizontal learning partnerships as a way to help them become better at what they do. She works as a a social learning theorist and consultant. The joy of her life is her two-year old grandson who lives in the United Kingdom. They stay in touch using Skype.

Etienne Wenger-Trayner is a social learning theorist and consultant. He helps organizations apply the principles of social learning to improve practice. He is married to Bev.

Etienne Wenger-Trayner is a social learning theorist and consultant. He helps organizations apply the principles of social learning to improve practice. He is married to Bev.

CREATING A COMMUNITY

Designing a community of practice approach to professional development is ultimately just creating a powerful learning space. Therefore, it is important to choose meeting structures and learning activities that promote collaboration, energy and participation.

Click each drop-down heading below to learn about various activities and structures that can help guide your community of practice.

Surfacing Topics

One of the first steps toward developing a community of practice is surfacing topics and prioritizing issues that are aligned with members’ needs and interests.

During our first #MyPD meeting, participants configured into groups by district and role to surface issues. They then distilled these issues into smaller topics and areas of action. Learn more about this process by clicking the Teachers’ Topics tab.

Core Leaders

A community of practice needs core leaders to serve as task masters for the whole group. It is important that this group of core leaders is not only people from the sponsoring district or organization — it needs to include members of the community. The core leaders build meeting agendas that guide collaborative learning and are responsive to the community’s needs. #MyPD core leaders were selected by simply volunteering.

Case Clinic

A case clinic is an opportunity for a community member to lead learning by bringing up a challenge they are experiencing for consideration by the whole group.

Engage the group with a clearly articulated challenge you are facing in your practice. Give just enough context for the group to ask follow-up questions. Their questions may surface underlying issues and root causes. Invite them to share stories about when they experienced something similar, how they dealt with it, what worked and what didn’t. What would they do in your shoes? Community members can offer advice and introduce alternative perspectives. Use small groups to think through questions or have a discussion using a fishbowl format.

Debate

A debate is a useful tool for allowing the community to grapple with different sides of a difficult topic.

A member can put forward a statement about something they are struggling with that may involve competing perspectives. Give sides time to prepare their arguments and use structured timing to move from side to side. After the debate, the group should reflect on the arguments made and come to a conclusion.

During our first community meeting we actually held a debate about whether the concept of #MyPD could even work!

Leadership Roles

Communities of practice can be intentional about continuous improvement by having each community member take on a leadership role, for periodic reflection and to ensure the community is on track. #MyPD used four leadership roles:

1. Value Detectives >> How can we create value and make it visible?

2. Community Keepers >> How do we build a community with the right members and the right relationships?

3. Social Reporters >> How do we create a shared and ongoing memory of community activities and learning?

4. External Messengers >> How do we communicate with external audiences and stakeholders?

Matrix

Building a matrix together is a great way to collect a large amount of information from different constituencies, such as grade-levels, subject-areas and schools.

Place labels for the different groups along the Y-axis. Each constituency group can contribute a question, which should be placed along the X-axis. Each group then spends time responding to all of the questions and placing their answers in the corresponding spot on the matrix. Rows and columns can be analyzed to compare practices and identify trends. Having groups color-code their answers can also be helpful:

- Green >> We do this well because…

- Yellow >> We want to learn how to do this better.

- Red >> We don’t do this (or don’t want to) because…

Landscape Mapping

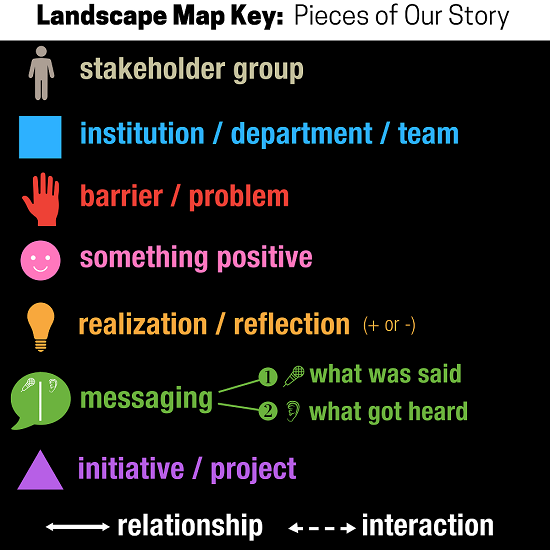

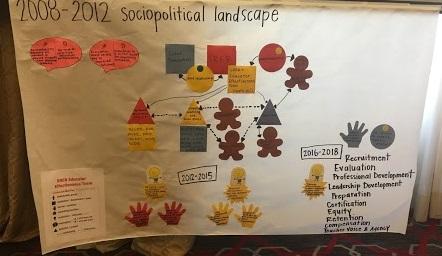

Landscape mapping is a useful exercise for visualizing relationships and connections. Landscape maps help people reflect on why a system or situation is the way it is.

Landscape maps use different pieces, each with a purpose: to help members think about a specific component of their story. Here are examples of the different symbols that can be used:

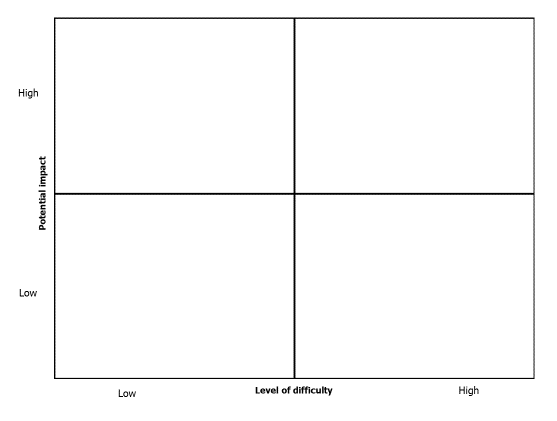

Action Strategic Planning Guidance

Don’t just tell community members to make plans and take action — give them tools to actually help them do it! This may include coaching and tangible resources.

For example, the template below can help working groups balance difficult priorities or make decisions about what to prioritize by reflecting on both impact and difficulty.

Incorporating structured resources can help groups capture their aspirations, requests, ideas and progress. Below are some examples of templates that SREB has shared with #MyPD members and members of our regional community of practice:

1. Innovation Groups Brainstorming Template >> link

2. Action Proposal Template >> link

3. Grant Budget Template >> link

4. Sustainability Planner Template >> link

Hands, Hearts and Stars

One of the core leaders of #MyPD led the whole group in an exercise designed to guide reflection about the community experience. Each person was given three shapes to write on:

1. Stars >> What have you or your group accomplished that you wouldn’t have accomplished had you not been involved in this community? What do you deserve a gold star for?

2. Hearts >> What is in your heart to improve on the rest of this year and into next year?

3. Hands >> What could you use a helping hand with? Community members then attached contact information where they felt they could serve as a helping hand to someone else.

Other Ideas

Other Ideas

During #MyPD, we incorporated many other activities, both formally and informally, to get working groups to reflect on their own work and engage their peers in soliciting information, exploring potential solutions and gathering data. Some examples of these activities include:

- reading groups and book studies

- role-playing

- polls and surveys

- producing tools and methods

- storytelling

- timeline-mapping

- demos

- hot topic discussions

- modeling practices

- field trips

Teachers’ Topics

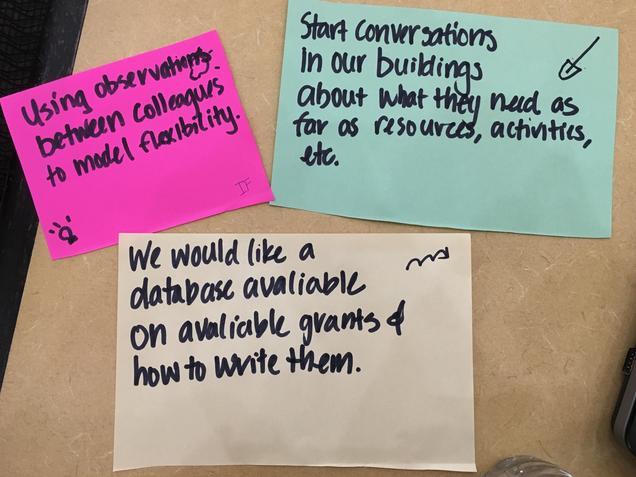

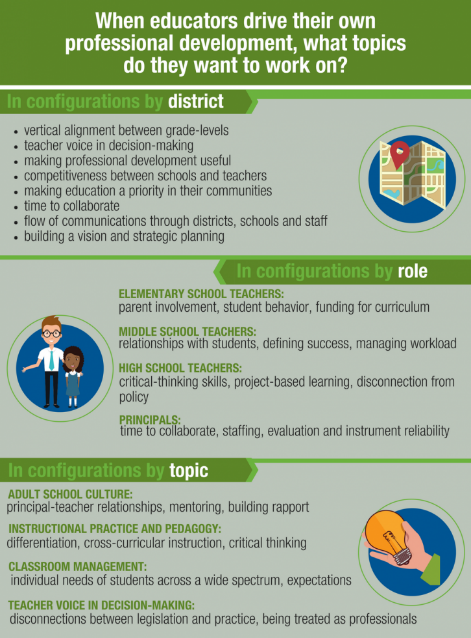

During our Oklahoma community’s first meeting, members regrouped into configurations such as by role, district and various topics of focus. These allowed community members to surface different issues that were important to them (right). The community reflected on the types of topics that arose and noticed that they could be grouped into two core themes:

During our Oklahoma community’s first meeting, members regrouped into configurations such as by role, district and various topics of focus. These allowed community members to surface different issues that were important to them (right). The community reflected on the types of topics that arose and noticed that they could be grouped into two core themes:

1. Professional development related to day-to-day teaching practice

2. The identity and role of educators systemically within the education field and society

But #MyPD (and any community of practice) is about more than identifying common areas of frustration — it’s about identifying common areas of motivation. Which of these identified areas could we take meaningful action on to work toward positive changes in practice? Social learning consultant and #MyPD facilitator Bev Wenger-Trayner explained:

“We won’t just get together to share tips and complain. Instead, how can we be strategic and punchy about making a difference?”

In subsequent #MyPD meetings, members reflected on which topics they felt were the most pressing, interesting and actionable — and we narrowed our huge list of topics down to five working groups.

Learn more about each working group by clicking the drop-down heading.

1. Classroom Culture

The Classroom Culture working group is focused on strategies for building the skills students need to succeed beyond the classroom. The group created a toolbox for educators with resources on a variety of subtopics, including physical classroom environment, emotional behavior, family background, and procedures. Classroom Culture Google Site >> link

The Classroom Culture working group is focused on strategies for building the skills students need to succeed beyond the classroom. The group created a toolbox for educators with resources on a variety of subtopics, including physical classroom environment, emotional behavior, family background, and procedures. Classroom Culture Google Site >> link

2. Growth Mindset

The Growth Mindset working group is focused on teachers’ and students’ ability to improve. Their goal is to explore what it means to have and implement a “growth mindset,” using the work of Carol Dweck as a jumping-off point. The group created a Facebook page to continue discussion and share resources. Growth Mindset Google Site >> link

The Growth Mindset working group is focused on teachers’ and students’ ability to improve. Their goal is to explore what it means to have and implement a “growth mindset,” using the work of Carol Dweck as a jumping-off point. The group created a Facebook page to continue discussion and share resources. Growth Mindset Google Site >> link

3. Instructional Flexibility

The Instructional Flexibility working group’s goal is to train and use staff to integrate new materials, tools and teaching methods so that students can participate in more flexible and purposeful instruction. The group’s action plan includes professional development sessions, structured collaboration between Special Education and General Education teachers, implementing a student “Move Up” day, and receiving grant money. Instructional Flexibility Google Site >> link

The Instructional Flexibility working group’s goal is to train and use staff to integrate new materials, tools and teaching methods so that students can participate in more flexible and purposeful instruction. The group’s action plan includes professional development sessions, structured collaboration between Special Education and General Education teachers, implementing a student “Move Up” day, and receiving grant money. Instructional Flexibility Google Site >> link

4. Two-Way Communications

The Two-Way Communications working group is focused on developing better communication among teachers, students, administrators, parents and communities. Ideas that they are interested in pursuing include a district-wide directory of personnel that lists each person’s area of expertise, anonymous open forums to voice concerns, and district town hall meetings that take place both regularly and in response to current events as they arise. Two-Way Communications Google Site >> link

The Two-Way Communications working group is focused on developing better communication among teachers, students, administrators, parents and communities. Ideas that they are interested in pursuing include a district-wide directory of personnel that lists each person’s area of expertise, anonymous open forums to voice concerns, and district town hall meetings that take place both regularly and in response to current events as they arise. Two-Way Communications Google Site >> link

5. Overcoming Challenges

The Overcoming Challenges working group is focused on increasing community involvement and building more positive perceptions of educators and public schools. First, the group pinpointed and described their three biggest challenges — money, outside opinions and parent issues. Then they identified ways to address each challenge and categorized them as quick and easy, moderate effort, or complex. They presented their ideas to district leaders and shared specific ways they could pitch in to help address each of the three main challenges. Overcoming Challenges Google Site >> link

The Overcoming Challenges working group is focused on increasing community involvement and building more positive perceptions of educators and public schools. First, the group pinpointed and described their three biggest challenges — money, outside opinions and parent issues. Then they identified ways to address each challenge and categorized them as quick and easy, moderate effort, or complex. They presented their ideas to district leaders and shared specific ways they could pitch in to help address each of the three main challenges. Overcoming Challenges Google Site >> link

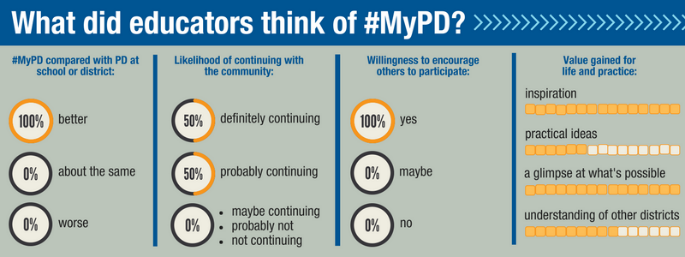

Feedback

After some of our #MyPD community meetings, teachers completed a survey. This is a snapshot of the results:

Our team also spoke with community members to gather qualitative information about the relative value the community was having for them. These are some of their thoughts and reflections:

“We seem to get stronger with each session. Our team gets better at communicating. It’s great to collaborate across grade levels.”

“I feel like this professional development allows me to have a voice. I like collaborating with others from different schools. I look forward to our next meeting.”

“I love the format of these meetings.”

“I am excited to have practical ideas that can be implemented by my team THIS school year. Lots will change as a result of my experiences here.”

“I am learning so much and applying it to my professional life.”

At the conclusion of our involvement in my #MyPD, we asked community members what they would want educators and leaders from other districts and states to know about the community of practice approach:

“It’s not the kind of workshop where you sit back and grade papers or, you know, get on your phone, on Facebook, or go to sleep. It’s a workshop where you have to be involved — but you also want to be involved.” – Teacher

“I felt I had ideas to share and they were listened to. An entire plan of action is being developed and pushed forward, and people are interested in hearing what you have to say. And something great might come out of it.” – Teacher

“The networking alone and finding people with the different skills and strategies that I have already adopted into my classroom has made a world of difference.” -Teacher

“It’s valuable. It’s worth your time, your money. Teachers need this to have their voice, to feel valued, to create the change that we need in our schools.” – Teacher

“I would encourage any district leaders to use this approach!” – District Assistant Superintendent

Tips and Advice

Want to implement teacher-led approach to professional development in your school building, district or state? These are some things we did that we found successful, some things we did that were not successful, and some things we wish we had done.

Click each drop-down heading below to learn from our mistakes, read our recommendations and build on what we’ve learned!

1. Let members set the goals.

Initially, we wanted a central theme of our approach to be putting teachers in the driver’s seat — and planned to create a community focused on the Oklahoma Teacher and Leader Effectiveness System. However, educators quickly informed us that although the evaluation system should lead to meaningful professional development, it was not currently being implemented that way, due to issues related to trust, communication and school culture.

Initially, we wanted a central theme of our approach to be putting teachers in the driver’s seat — and planned to create a community focused on the Oklahoma Teacher and Leader Effectiveness System. However, educators quickly informed us that although the evaluation system should lead to meaningful professional development, it was not currently being implemented that way, due to issues related to trust, communication and school culture.

Educators suggested the community work together to break down these barriers before taking on the evaluation system itself. We decided to set aside our original intention and allow the priorities to shift to what community members truly needed. If we had not let members create groups to tackle challenges related to trust, communication and culture, the community would not have come together as it did.

RECOMMENDATION >> It is not uncommon for there to be tension between the stated goals of a funded project and the goals of the practitioners. When using a community of practice approach with educators, the sponsor’s goals need to be flexible enough for participants to take ownership of the topic in ways that make sense to them and align with their underlying needs.

2. Incentivize continuity.

The community really took off when members started to experience continuity. After we didn’t see a great deal of continuity between the first two meetings, we realized that we had focused too much on recruiting new members and overlooked retaining current members. We implemented new messaging strategies to target previous participants and focused on three main forms of continuity:

The community really took off when members started to experience continuity. After we didn’t see a great deal of continuity between the first two meetings, we realized that we had focused too much on recruiting new members and overlooked retaining current members. We implemented new messaging strategies to target previous participants and focused on three main forms of continuity:

1. Participation >> We incentivized return by providing monetary stipends. This helped send the message to teachers that we valued their time and participation. Teachers were excited to come back to #MyPD and find the same people committed to working on the same theme with them, meeting after meeting.

2. Making a Difference >> Teachers were inspired when they realized the topic they chose was something they could keep working on until they made progress; it was not simply a one-off group discussion or activity.

3. Shared Memory >> The use of online spaces began to make sense to teachers when they saw how it served as a consistent tool for collaboration, a workspace, and a place for their group to document shared memories and progress.

RECOMMENDATION >> A community of practice kicks off when people see that they are participating in an ongoing learning journey, with familiar faces and a shared commitment to making a difference. Be intentional about continuity of participation and view learning as something that takes place over a series of meetings, not in detached events.

3. Be purposeful about diversity.

In initial interviews that we conducted, teachers and principals expressed enthusiasm about the concept of participating in a community together. Four principals came to the first meeting, and while they did find value in connecting with other principals, the community ended up focusing very much on teachers’ needs and interests. This reflects a tension inherent in complex communities. Looking back, it would have been more productive if we had held simultaneous but separate meetings for administrators and teachers at the beginning and, over time, integrated them in a careful manner.

In initial interviews that we conducted, teachers and principals expressed enthusiasm about the concept of participating in a community together. Four principals came to the first meeting, and while they did find value in connecting with other principals, the community ended up focusing very much on teachers’ needs and interests. This reflects a tension inherent in complex communities. Looking back, it would have been more productive if we had held simultaneous but separate meetings for administrators and teachers at the beginning and, over time, integrated them in a careful manner.

RECOMMENDATION >> If a community invites members who represent different constituencies, it is important that all find value in participating. This calls for substantial and productive interactions and learning within constituency groups before this can take place across the groups.

4. Find the right balance of data.

At the beginning, we aspired to create different types of value by supporting the #MyPD community. We used Wenger-Trayner’s Value-Creation Framework to articulate our aspirations and reviewed them after collecting some initial data during school visits. We hoped to have a baseline to evaluate our achievements and allow the community to see for themselves the progress they were making. We also conducted entrance and exit surveys at the first few meetings.

At the beginning, we aspired to create different types of value by supporting the #MyPD community. We used Wenger-Trayner’s Value-Creation Framework to articulate our aspirations and reviewed them after collecting some initial data during school visits. We hoped to have a baseline to evaluate our achievements and allow the community to see for themselves the progress they were making. We also conducted entrance and exit surveys at the first few meetings.

However, this project was limited in time and scale. This made us realize that we needed to focus more energy on giving teachers a productive experience, and less on collecting data for future use. We didn’t abandon data altogether; it just took different forms. At each meeting, we provided time for working groups to share information about which ideas members were trying out in their schools. We didn’t systematically collect this information for deep analysis, but some of these value-creation stories are included in a short video. We estimate that it would take one or two more years for us to be able to collect meaningful data on the impact of the project at scale.

RECOMMENDATION >> Be realistic about the kind of data that you can collect with limited resources, and be consistent about using it. Keep in mind that the collection of data should be in service of the community’s learning, rather than a stand-alone goal.

5. Think long-term.

In the short- and medium-term, teachers gained a sense of agency and valued working together on issues of common concern that they had chosen themselves. In March 2018, many participants reported that they had already made changes at their schools as a result of #MyPD. However, these wins do not necessarily translate into an ongoing, sustainable community. It took at least a year to adjust expectations about what constitutes professional development and to trust the process of putting teachers in the lead. It would have taken two or three more years to build internal leadership in the group, so they would be better prepared to take over and continue making a difference. Additional years would be necessary to observe the effects of changes in practice made by members.

In the short- and medium-term, teachers gained a sense of agency and valued working together on issues of common concern that they had chosen themselves. In March 2018, many participants reported that they had already made changes at their schools as a result of #MyPD. However, these wins do not necessarily translate into an ongoing, sustainable community. It took at least a year to adjust expectations about what constitutes professional development and to trust the process of putting teachers in the lead. It would have taken two or three more years to build internal leadership in the group, so they would be better prepared to take over and continue making a difference. Additional years would be necessary to observe the effects of changes in practice made by members.

RECOMMENDATION >> While it is possible to cultivate a group like #MyPD that achieves some results in two years, three to five years of ongoing support are likely needed to develop a sustainable community.

6. Recognize the importance of trust-building.

When inviting people into a community of practice, it is important to convey that this is a genuine learning partnership with no hidden agenda. This is especially true if the community is being initiated by an outside organization, like SREB. In September 2016, we had a series of meetings with school district leaders that helped us gain a better understanding of the context, and develop partnerships between SREB and strategic stakeholders. In November 2016, we connected with administrators and teachers from 13 schools across the three participating districts during our first site visit.

When inviting people into a community of practice, it is important to convey that this is a genuine learning partnership with no hidden agenda. This is especially true if the community is being initiated by an outside organization, like SREB. In September 2016, we had a series of meetings with school district leaders that helped us gain a better understanding of the context, and develop partnerships between SREB and strategic stakeholders. In November 2016, we connected with administrators and teachers from 13 schools across the three participating districts during our first site visit.

In retrospect, we wish we had visited every school in the three districts to represent the project properly and to conduct informational sessions prior to our first meeting. This would have required at least a week-long site visit. Because our outreach timeline was tight, a number of people came to our first #MyPD meeting without a clear idea of what to expect. A proper preparation, not including the necessary planning on our end, would have required at least six months.

RECOMMENDATION >> Allocate plenty of time on the ground to prepare before launching the community. This needs to be enough time to have personal conversations, build relationships, clarify intentions, and learn about the perspectives of both local sponsors and potential members.

7. Partner locally.

Building a community of practice as an outsider has both upsides and downsides. One upside is that we were not influenced by local politics and the history of the districts. However, we think the project would have benefited from a partnership between us and a local entity who could provide more regional, on-the-ground connections. Although we had the support of the state department and district superintendents, partnering with the local teachers’ association or a similar organization may have helped us to build trust more quickly. This organization would also be in a strategic position to continue supporting the community after we left.

Building a community of practice as an outsider has both upsides and downsides. One upside is that we were not influenced by local politics and the history of the districts. However, we think the project would have benefited from a partnership between us and a local entity who could provide more regional, on-the-ground connections. Although we had the support of the state department and district superintendents, partnering with the local teachers’ association or a similar organization may have helped us to build trust more quickly. This organization would also be in a strategic position to continue supporting the community after we left.

RECOMMENDATION >> Do your research about local organizations and individuals who can facilitate access and increase the chances of long-term sustainability.

8. Ask about scheduling.

By the end of the project, we had found a rhythm for the meetings that worked well for teacher participation. But it took some trial-and-error. We hosted the first two meetings on weekdays and funded substitute-teacher reimbursements. Although we saw good participation during these meetings, we also received feedback that teachers had difficulty leaving their classrooms and missing meetings.

By the end of the project, we had found a rhythm for the meetings that worked well for teacher participation. But it took some trial-and-error. We hosted the first two meetings on weekdays and funded substitute-teacher reimbursements. Although we saw good participation during these meetings, we also received feedback that teachers had difficulty leaving their classrooms and missing meetings.

Using this feedback, we made the decision to offer the meetings on Saturdays. We gave attendees a stipend and offered free daycare for participants’ children. These changes attracted a committed group of teachers who were able to attend without interference from classroom commitments.

In addition, we received positive feedback when we began rotating the geographical location of the meetings, so that one group of teachers did not always have to travel the farthest. We also offered morning and lunch refreshments at each meeting. These small things had a large effect on increasing both participation and satisfaction.

RECOMMENDATION >> Use educators’ feedback and be prepared to keep exploring different options until you find the logistical conditions that work best for the community.

9. Integrate online tools to make collaboration easy.

We created a WikiSpaces site as a “home base” for shared notes, resources, photos and announcements. All members were able to make edits to this site. This worked well, promoting continuity across meetings and reinforcing a sense of shared ownership of the content and process. The site was primarily used during meetings for groups to record their discussions directly. People generally do not expect to use online tools in real time to document their face-to-face interactions, so it took some persistence on our part until its usefulness became evident and the tool became a seamless part of the process. These are some ways in which the site was included in the community:

We created a WikiSpaces site as a “home base” for shared notes, resources, photos and announcements. All members were able to make edits to this site. This worked well, promoting continuity across meetings and reinforcing a sense of shared ownership of the content and process. The site was primarily used during meetings for groups to record their discussions directly. People generally do not expect to use online tools in real time to document their face-to-face interactions, so it took some persistence on our part until its usefulness became evident and the tool became a seamless part of the process. These are some ways in which the site was included in the community:

Meeting Preparation:

- meeting registration

- accessing meeting agendas and resources

- compiling members’ contact information and brief biographies

During Meetings:

- a backdrop projected on screen as each meeting progressed containing instructions for activities and groups

- pages for each group to take notes

- sharing photos and work templates

Coincidentally, at the end of the project, WikiSpaces announced they would be closing down. So we transferred all of the content to a new #MyPD Google Site.

RECOMMENDATION >> Weave the use of online tools into face-to-face activities to establish continuity. Model the use of these tools consistently. Integrate them into meeting activities until they become a part of the community’s practice.

10. Allow venting.

During the first few #MyPD meetings, we helped members arrange themselves into various groupings — such as by district, grade-level and role — in order to surface their common problems of practice. Unsurprisingly, these groupings elicited a lot of what could be considered “complaining.” It was important for us to recognize that this served an important purpose; venting about an area of need can help people to better understand multiple facets of an issue and the impact these have on various stakeholders. In this way, venting can actually be a form of analysis — and analysis is a prerequisite to planning strategically and taking action. Venting can also be a bonding experience. Allowing #MyPD members time and space to vent about their topics of choice helped them connect with one another and uncover areas of opportunity for them to take meaningful action.

During the first few #MyPD meetings, we helped members arrange themselves into various groupings — such as by district, grade-level and role — in order to surface their common problems of practice. Unsurprisingly, these groupings elicited a lot of what could be considered “complaining.” It was important for us to recognize that this served an important purpose; venting about an area of need can help people to better understand multiple facets of an issue and the impact these have on various stakeholders. In this way, venting can actually be a form of analysis — and analysis is a prerequisite to planning strategically and taking action. Venting can also be a bonding experience. Allowing #MyPD members time and space to vent about their topics of choice helped them connect with one another and uncover areas of opportunity for them to take meaningful action.

RECOMMENDATION >> Recognize that venting is okay and is a natural part of the community process, especially at the beginning. Give educators time and space to both express and explore their complaints, without cutting them off. These complaints will serve as the foundation of their focus areas and action plans.