No Longer Alone

Instructional Coaches Find Their Peers at SREB Conference

Being an instructional coach can be a lonely journey.

Just ask LaTonya Bolden, a former high school math and science teacher who now works with teachers and schools across the country as a school improvement coach for SREB.

Becoming a teacher-coach wasn’t always easy for Bolden, who suddenly had to work with teachers in academic subjects outside her own and with teachers in early- and middle-grades schools. She also found herself mainly working with adults all day.

“I miss the kids, I miss that daily interaction that I had with the students, because a lot of times that’s what kept me going,” Bolden said. “Interacting with adults is a little different.”

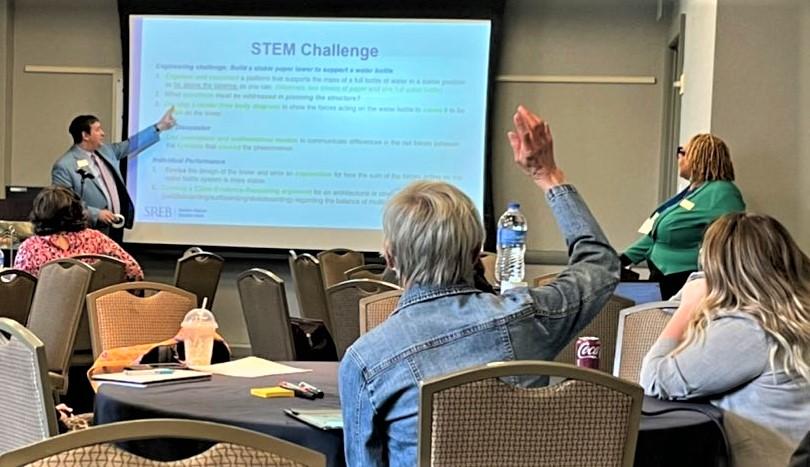

Bolden and other educators now working as instructional coaches — who focus on helping K-12 teachers hone and improve their classroom instruction — gathered in May for the first SREB conference designed just for them.

Kicking off the inaugural Coaching for Change conference at the Georgia Tech Hotel and Conference Center in Atlanta, Scott Warren, the division director for Making Schools Work at SREB, told the audience that instructional coaches have a critical role in helping schools and educators ramp up their goals and expectations.

Many schools appoint reading, math or other specialists without considering how those educators can best work with others. “Coaching by chance” is too prevalent, Warren said. “Good coaches plan.”

SREB President Stephen Pruitt added that SREB thrives by providing such events that bring educators together to solve common challenges, and that the conference will likely grow in the future — if this year’s waiting list was any indication.

The nitty gritty of coaching

Participants at the conference attended sessions for coaches in math, science and STEM, literacy, broader instruction, and whole school coaching.

Elizabeth Jordan, a coach in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in North Carolina, led the session with Bolden. She’d been a teacher for 22 years before switching to coaching for several schools, she said.

“When we transition from teacher to coach,” Jordan said, “things change.”

Bolden asked the coaches to list the obstacles they were facing in their work.

Coaches responded by saying they now had to figure out how to coach their former teacher colleagues. Teachers often see them as an administrator or evaluator when their role is only to provide help and support for educators.

The coaches said they also lacked confidence or preparation for their new assignment, that their principals or even school systems don’t fully understand their role, and that some teachers don’t see the need for change or improvement.

“When we transition from teacher to coach, things change.” - North Carolina educator Elizabeth Jordan

In their session for new coaches, Bolden and Jordan asked several dozen coaches to rank in importance 10 common roles for an instructional coach. While every situation is different, here’s how a group of four instructional coaches from Georgia ranked their priorities:

1. Learner

2. Classroom supporter

3. Mentor

4. Catalyst for change

5. Instructional strategist

6. Learning facilitator

7. Curriculum specialist

8. Data analyst

9. Resource provider

10. School/district leader

One of the most important questions an instructional coach can ask a teacher is how he or she is doing, Jordan said — and then waiting for a detailed response. For instructional coaches, building relationships with adults matters as much as when teachers connect with a student, she said.

The self-doubt of “imposter syndrome” is also common, Jordan said.

That’s why better preparation and continued learning for instructional coaches is essential.

“Coaches need coaching,” Bolden said. “Part of being a great coach is also being transparent… I’m very open and transparent about what my struggles are as a teacher.”

“Coaches need coaching.” – SREB School Improvement Coach LaTonya Bolden

What qualities do coaches want to emerge in their work? Bolden asked the coaches to provide their own answers. They included:

- Working with teachers, students, parents and others so that improvement is infectious and “becomes the culture of the school.”

- Building a welcoming group with hardworking people, surrounded by the resources necessary for success.

- Fostering a safe place that allows for risk-taking — each day is well-planned and there are no hard feelings among colleagues learning from each other.

- Forgiving yourself and allowing yourself some grace (because we’re often our own worst critics ).

For Jordan, as an instructional coach, she wanted to ensure “people see me as someone (they) can continue to learn from” by working together.

Setting the standard

These challenges are why Page and her colleague Jean Quigg developed the first national standards and certification levels for school improvement specialists — otherwise known as instructional coaches.

Just as “a rural kid can’t be what they cannot see,” many coaches can’t envision a successful path because they’ve never seen one for that role, Page said.

“You can’t learn to fly a plane without practice,” she added.

The most common pitfall among instructional coaches, Page said, is not having a plan.

While the standards for instructional coaches aren’t in any particular order, many coaches begin with this standard, Quigg said: “Analyze and apply critical judgement.”

Determining the situation coaches face in a school or district is a key step before an educator can prepare to guide others in their work, added Quigg, now with The Institute for Performance Improvement.

Often a school’s challenges are many, with multiple causes, requiring a suite of solutions, she said.

Training for coaches

Courtney Shealy Hart, a two-time Olympic gold medal winner and the head coach of swimming and diving at Georgia Tech, shared her strategies for coaching adults and athletes.

Most of all, she establishes clear, rigorous expectations, while also being positive and upbeat.

“I try to learn something from somebody every single day,” whether from a coach, athlete, or someone else, Hart said. “My job… is to keep the big picture in mind and be flexible.”

She explained her system for planning, goalsetting and holding herself and others accountable. “Have a focus — planning, planning, planning. We constantly plan,” she said, even using an app to interact with athletes about their daily workout plans. “I take notes throughout the practice, so I can go back and make adjustments next time.”

“Teach something every day, learn something every day, and always analyze and improve. Create those small steps to help you get there. Man, it’s amazing when you do.” – Courtney Shealy Hart, head coach of swimming and diving at Georgia Tech

Hart showed the audience her 52-week spreadsheet that breaks down long-term, short-term and even daily goals and guideposts throughout the year.

She crafts a plan for each season, breaking down smaller goals into each week. She holds brief planning meetings with each assistant coach and daily check-in discussions, too.

Planning helps “explain the why of what we do,” Hart said. “Communication is huge.”

While based on individual performance, swimming is a team sport, she added. Personal relationships are important, so she invites her staff to her home every couple of months for dinner and discussion.

Inspiring improvement

The most challenging conversations are around when someone needs improvement, she said: “All successful people need improvement.” If it’s a long-term issue, she’ll take a coach or athlete away from the pool — or away from the office.

“Make that space more neutral for them,” she suggested. Then explain the specific deficiency and develop a plan to address it.

“It’s their goal,” Hart said. The question becomes: “How can I help you get to where we need to be?”

Maybe the plan needs modifying, or maybe the person needs encouragement or to look at a goal differently. Encourage the good parts and any movement in the right direction, then build on that, she said. “Ask them how I can make us better… how can I hold you accountable?”

What if they don’t improve? “Help them find out what they do well and then what they need to improve on.”

Sometimes, Hart may need to change her focus or expectations. While the goal is always to shoot for the stars — making the NCAA tournament and having an opportunity to win it all — “it’s OK if we don’t get there all the time, every single day.”

Swimmers’ heads are always down, she said. They’re staring at a black line at the bottom of the pool. That’s why they need coaching, and it’s why coaches need to be prepared to help those performers do their best.

“Teach something every day, learn something every day, and always analyze and improve,” Hart said. “Create those small steps to help you get there. Man, it’s amazing when you do.”

Because of the demand and many positive reviews by participants in the May 2022 conference, SREB is already planning a second Coaching For Change conference for spring 2023.